Class of 1916 Sundial

Directly in front of Dallas Hall is the Class of 1916 Sundial. But over the years it has developed a problem: there’s nothing on it to cast a shadow!  The piece that’s missing is called the style — a thin rod whose shadow lines up with one of the hour markings on the face of the sundial. Fortunately, you can use any relatively thin, straight object, like a pen from your pocket, as a substitute style, as long as you put it in the correct place. If you look at the top of the sundial, it’s pretty clear where the style was attached (the center of the disk), but how do we know what angle we should hold the pen at? Clearly it will cast a shadow in a different place depending on the angle.

The piece that’s missing is called the style — a thin rod whose shadow lines up with one of the hour markings on the face of the sundial. Fortunately, you can use any relatively thin, straight object, like a pen from your pocket, as a substitute style, as long as you put it in the correct place. If you look at the top of the sundial, it’s pretty clear where the style was attached (the center of the disk), but how do we know what angle we should hold the pen at? Clearly it will cast a shadow in a different place depending on the angle.

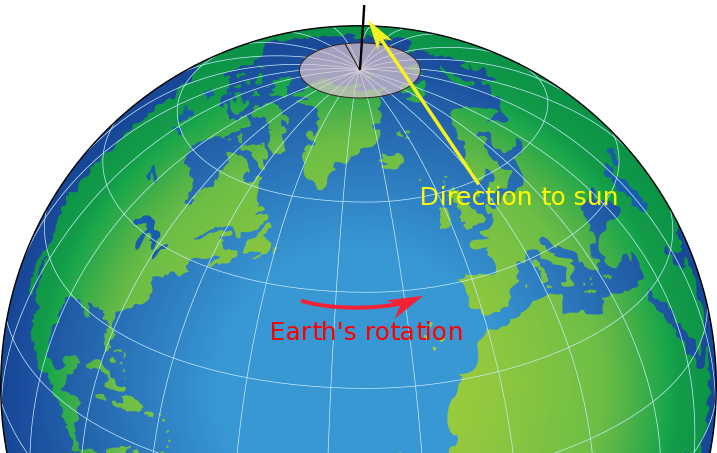

Answering this question just requires a little bit of information about how a sundial works, and a little bit of geometry. The easiest sundial to imagine is one sitting exactly at the North Pole with its style pointing straight along the axis of the Earth’s rotation and its face flat on the ground (well, or icecap). Over the scale of one day, the Sun is pretty close to fixed in space relative to the Earth, so as the Earth rotates, the shadow of the style falls successively on different points on the face of the sundial, allowing us to tell the time. (In fact, during the summer at the North Pole, you can use such a sundial 24 hours a day. And what’s more, because the Earth rotates counterclockwise when viewed from the North Pole, the shadow will appear to move clockwise on the face of the sundial, which is where the “clockwise” direction came from in the first place!) This diagram should make things a little clearer: If you now imagine moving that sundial anywhere else on the globe (Dallas, say), it will work the same way as long as that shadow-casting rod, the style, remains pointing in the same direction in space (parallel to the Earth’s rotational axis). That means the style will not be perpendicular to the ground at any other location (except for the South Pole), although it will always point due North. For example, at the Equator, the style would be exactly parallel to the ground (and the shadow would move horizontally across the dial, which would have to be mounted below the style so that the style actually casts a shadow). That would look something like the below, which is in a garden in Singapore, a city that lies very nearly on the Equator.

If you now imagine moving that sundial anywhere else on the globe (Dallas, say), it will work the same way as long as that shadow-casting rod, the style, remains pointing in the same direction in space (parallel to the Earth’s rotational axis). That means the style will not be perpendicular to the ground at any other location (except for the South Pole), although it will always point due North. For example, at the Equator, the style would be exactly parallel to the ground (and the shadow would move horizontally across the dial, which would have to be mounted below the style so that the style actually casts a shadow). That would look something like the below, which is in a garden in Singapore, a city that lies very nearly on the Equator. What about between the Equator and the North Pole? What angle should the style make with the ground? This diagram of a cross section of the Earth should help make that clearer.

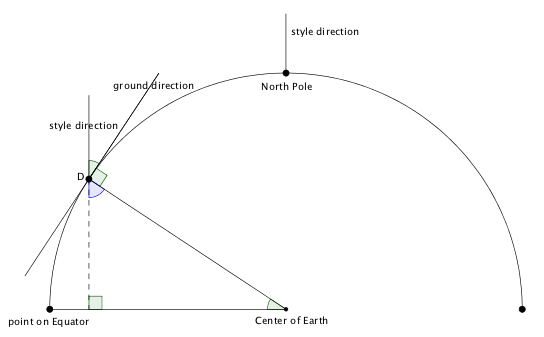

What about between the Equator and the North Pole? What angle should the style make with the ground? This diagram of a cross section of the Earth should help make that clearer. Because the ground direction is perpendicular to an imaginary line to the center of the Earth, the angle between the style and the ground at D is complementary to the angle shown in blue. But because the triangle shown with the dotted line is a right triangle, the angle in blue is also complementary to the angle that D makes with the Equator at the center of the Earth. So since they’re complementary to the same angle, the style angle is equal to the angle that D makes with the Equator. But that angle has a familiar name that makes it easy to look up: it’s called the latitude at the point D. So if D is Dallas, then we can look up the latitude as (approximately) 33°, and then lets us know to angle our pen-as-style at 33 degrees to the ground to read off the time. Oh, and don’t forget: the Sun doesn’t go on daylight savings time, so if that’s in effect, subtract an hour from the indicated time.

Because the ground direction is perpendicular to an imaginary line to the center of the Earth, the angle between the style and the ground at D is complementary to the angle shown in blue. But because the triangle shown with the dotted line is a right triangle, the angle in blue is also complementary to the angle that D makes with the Equator at the center of the Earth. So since they’re complementary to the same angle, the style angle is equal to the angle that D makes with the Equator. But that angle has a familiar name that makes it easy to look up: it’s called the latitude at the point D. So if D is Dallas, then we can look up the latitude as (approximately) 33°, and then lets us know to angle our pen-as-style at 33 degrees to the ground to read off the time. Oh, and don’t forget: the Sun doesn’t go on daylight savings time, so if that’s in effect, subtract an hour from the indicated time.